Privileged Identity Playbook

| Version Number | Date | Change Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1.2 | 12/29/2022 | Fixed Acknowledgment word usage. |

| 1.1 | 12/15/2022 | Clarify activities around automated discovery of entitlements and microservices. |

| 1.0 | 09/25/2022 | Initial Draft. |

This playbook is a collaboration among the General Services Administration Office of Government-wide Policy, Federal Identity and Cybersecurity Division, Federal Chief Information Security Officer Council ICAM Subcommittee, and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) Continuous Diagnostic and Mitigation (CDM) Program.

Executive Summary

Privileged users are unique user types that perform various security-related duties. As such, privileged accounts are most likely to be targeted by cybercriminals or abused by malicious insiders. Unwanted behavior or compromised privileged accounts are responsible for the most high-profile federal and private security breaches. It is a critical Identity, Credential, and Access Management (ICAM) capability to secure privileged access.

There are three prominent use cases to identify a privileged account or user:

- Administrators manage IT infrastructure, high-value assets (HVA) resources, and core systems such as maintenance activities on human resource applications or databases.

- Help desk personnel with escalated privileges to perform security-relevant processes on endpoints, such as installing software on user laptops or changing endpoint configuration settings. Managers that approve or recertify access or accounts.

- Managers who approve or recertify access or accounts.

Privileged users are managed as distinct and separate identities to decrease the risk and impact of agencies’ missions if compromised. Cyber security risks can be imposed on an organization without properly managing privileged users and accounts. For example, employees and contractors with privileged access can:

- Jeopardize sensitive information or infrastructure, whether knowingly or unknowingly.

- Have the potential to compromise all three core elements of information security: availability, confidentiality, and integrity.

This Privileged Identity Playbook is a practical guide to help federal agencies implement and manage a privileged user management function as part of an overall agency ICAM program. Privileged user management will identify, track, monitor, and audit privileged users and accounts to actively decrease the cyber risk to an agency’s mission. Agencies can use this playbook to help plan and implement privileged user management following government-wide best practices. This playbook includes a four-step process aligned with the Federal Identity, Credential, and Access Management (FICAM) Architecture designed for insider threat, ICAM, and risk management professionals interested in identifying best practices for mitigating privileged user risk. Agencies are encouraged to tailor this playbook to fit their unique organizational structure, mission, and technical requirements. Other IT program participants, including cybersecurity program managers, may value incorporating this playbook approach in their planning. This playbook supplements existing federal IT policies and builds upon the Office of Management and Budget Memorandum (OMB) Memo 19-17 - Enabling Mission of Delivery through Improved Identity, Credential, and Access Management and OMB Memo 22-09 - Federal Zero Trust Strategy, as well as existing federal identity guidance and playbooks.

Key Terms

Below are key terms used throughout this playbook. A linked term denotes an official term from a federal policy, NIST Glossary, or NIST publication. An unlinked term is defined for this document.

- Account compromise is the unauthorized use of an account to disclose, modify, substitute, or use sensitive information.

- Insider threat is the potential for an insider to use their authorized access, wittingly or unwittingly, to harm the security of the United States. This threat can include espionage, terrorism, unauthorized disclosure of national security information, or the loss or degradation of departmental resources or capabilities.

- Functional privileged users can access information resources provided by the application and approval workflows, such as approving access requests.

- Privileged account is a system account used by a privileged user. A privileged account can belong to a single endpoint, network device, domain, database, or application. A privileged account can run privileged commands which involve the control, monitoring, or administration of a system, including security functions and associated security-relevant information.

- Privilege compromise is either an adverse action of a privileged user or account through an insider threat or an account compromise.

- Privileged User is authorized (and therefore, trusted) to perform security-relevant functions that ordinary users cannot perform—also known as a privileged IT user, privileged network user, or superuser.

- Unauthorized Privilege escalation exploits a bug or flaw that allows for a higher privilege level than what would usually be permitted.

Disclaimer

This playbook is informative. The General Services Administration Office of Government-wide Policy, in collaboration with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Continuous Diagnostic and Mitigation (CDM) Program and the Federal CISO Council ICAM Subcommittee developed this playbook with input from federal identity and security practitioners. This playbook is limited to high-level guidance for privileged users accessing Federal Government information systems. This playbook shouldn’t be interpreted as official policy or mandated action and doesn’t provide authoritative definitions for IT terms.

Protect Federal Identities and Logical Assets

Government employees and contractors need a privileged account to perform necessary administrative and security functions, which creates an inherent risk of insider threat or account compromise. As a result, agencies should implement privilege user controls that reduce this risk without hindering their ability to carry out assigned job duties. In creating a secure physical and virtual workplace for privileged users, agencies align efforts with the FICAM Architecture. The following are the four primary high-level steps to establish or enhance an agency’s privileged user management function of an agency’s ICAM program.

-

Develop a privileged user policy to define or assess policies, strategies, and technologies used to control, monitor, and secure elevated access to critical agency resources. This step is intended to reduce or avoid risk and impact on the agency’s mission. Agency executives must understand why privileged user management is essential and the risks associated with elevated access. This step also includes engaging agency stakeholders and staying abreast of insider threats and ICAM best practices through government-wide groups.

-

Define and identify privileged users as people, devices, and accounts with elevated access to an agency’s resources to determine and set the appropriate level of privileged access controls. Privileged accounts can be anywhere across a network, system, or the cloud. Track and audit privileged user activity regularly.

-

Implement as an Enterprise ICAM Service for a holistic management approach. Implementing ICAM best practices and additional countermeasures to prevent privileged user and account misuse, abuse, or compromise can provide comprehensive, integrated protection of agency resources.

-

Prioritize and execute privileged identity services and capabilities with integral governance over sensitive systems and the ability to monitor how an agency’s resources are accessed. Like most IT initiatives, this is a journey. Threats change, and agencies must reassess their privileged user management and adapt.

Implementing privileged user management may require a multi-year project to add capabilities and services based on your agency’s risk and budget. The DHS CDM Program is one of the primary means for most agencies to architect and implement privileged access management.

Is this Privileged Access Management or Account Security?

Different vendors may use other terms for their products. Some vendors may use Privileged Access or Account Management (PAM), Privileged Identity Management (PIM), Privileged Security, or something in between. For the intent of this playbook, the agnostic privileged identity is used to encompass different privileged activities.

Step 1. Develop a Privileged User Policy

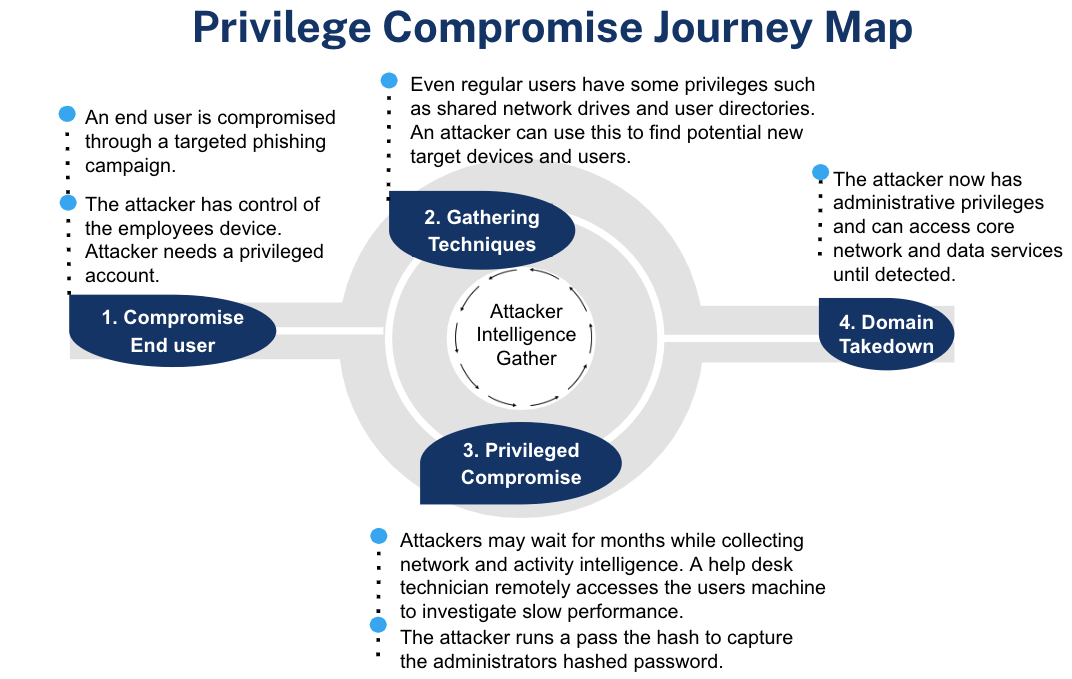

Privilege compromise within an agency’s privileged user population can significantly hurt its mission. See Figure 1 for the Privilege Compromise Journey. Poor management of an agency’s privileged user population can lead to catastrophic events such as:

- exfiltration of sensitive or classified data;

- rendering a system inoperable through configuration changes; or

- creating and granting shadow administrator accounts for continued access.

Figure 1: Privilege Compromise Journey Map

Privilege compromise comes in two forms:

- Insider threat

- Account compromise

Insider Threat

An insider threat is when a government employee or contractor accidentally, complacently, or maliciously uses their privilege to commit a harmful action against an agency. Privileged user management is grounded in implementing, monitoring, and reporting such insider-based threats. The table below provides the definitions and indicators of the three insider threat classifications.

Table 1: Insider Threat Classification, Definition, and Examples

| Insider Threat Classification | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Accidental | Lack of awareness regarding policies, procedures, and technical competencies. | 1. Unknowingly installs unapproved software. 2. Use privileged accounts for anything other than official administrative actions. 3. Accidentally deletes all data with a single command. |

| Complacent | Overall lax or careless approach to security. | 1. Create user accounts and assign privileges without the appropriate review and approval. 2. Share system account passwords. |

| Malicious | Intentionally disrupt, threaten, or endanger an agency’s activities or assets. | 1. Unwanted, purposeful disclosure or of information. 2. Introduce malicious code, malware, Trojan horse, and viruses. 3. Destroy or modify system audit logs. |

Insider Threat Mitigation

Because of privileged users’ elevated access, unwanted behavior by these individuals can significantly compromise agency assets or operations. Understanding insider threat classifications and unwanted behavior will support implementing an agency’s privileged user management. A combination of procedural and technical measures can help agencies reduce the range of unwanted behavior.

Account Compromise

An account compromise is the unauthorized use of an account to perform an unwanted behavior. Table 2 includes examples of unwanted behavior.

Table 2: Unwanted Behavior Classification, Definition, and Examples

| Unwanted Behavior Classification | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Fraud | Unwanted use, modification, addition, or deletion of agency data for personal gain. | A database administrator modifies data without authorization on the pretense of fixing corrupt data. |

| Espionage | Sharing restricted information to aid a foreign actor or harm the U.S. Government. | An external actor uses a compromised account to steal data. |

| Sabotage | Purposely inflicting harm on an organization. | An external actor uses a phished credential to load ransomware onto a payment system. |

| Intellectual Property Theft | Stealing intangible assets (e.g., discoveries, inventions, designs) from an organization. | Cloud administrators use elevated access to steal proprietary information. |

| Unwanted Information Disclosure | A communication or physical transfer of information to a recipient who is not authorized to access the information. | A system administrator creates a “backdoor” account to access and release classified information inappropriately. |

Agency Governance

A privileged user policy interacts with multiple initiatives across an agency. Examples include:

- High Value Asset (HVA) - OMB Memo 19-03 outlines requirements to identify, track, and manage an agency’s most critical assets. Guidance from CISA recommends using individual accounts, logging key security events, and implementing multi-factor authentication for all HVA users, particularly privileged users.

- Insider threat - Includes programs to detect and prevent unauthorized disclosure of sensitive information. An insider threat program provides, access to information, centralized information integration, analysis, response, insider threat awareness training, and user activity monitoring on government computers.

- Cybersecurity/ICAM - Responsible for identity, credential, and access management services and coordination. Privileged Access Management is a service area under Access Management.

- Continuous Diagnostic and Mitigation (CDM) - Cybersecurity tools, integration services, and dashboards to help agencies reduce the attack surface, increase visibility into cybersecurity posture, improve response, and streamline FISMA reporting.

- Risk Management - Identify and track the implementation and operation of security controls.

Privileged user management should encompass all privileged users within a Chief Information Officer (CIO) ‘s Federal IT Acquisition Reform Act (FITARA) responsibility, including enterprise and mission applications.

Who's your privileged user champion?

Agencies should choose a champion to advocate for their privileged user management process. The champion should either have executive support and/or is an executive who can effectively encourage, support, and direct implementation. Conduct a pilot by identifying an initial group of privileged users and accounts supporting the change management process required to overcome change resistance. Implement the change incrementally within the champion organization and expand to other privileged user groups based on readiness. Stay focused on your defined program objectives to win greater agency-wide support. Conduct after actions after each deployment to ease subsequent integrations.

Policy Objectives

Even though agency missions may differ, the objectives of privileged user management are relatively similar. The following strategic and tactical objectives are used as a starting point to plan privileged user management.

Strategic Objectives

- Identify vulnerabilities and risk factors to protect HVAs and other assets.

- Limit successful attacks by preventing network takeover and lateral movement.

- Secure sensitive workloads both on-premises and in the cloud.

- Prevent sensitive data loss and exfiltration.

- Comply with existing and evolving federal requirements for people and non-person accounts.

Tactical Objectives

- Discover, inventory and validate privileged account scope and numbers.

- Minimize the number of privileged users and remove all orphaned privileged accounts.

- Limit both duration of privileged account log-in and privileged account validity.

- Enforce least privilege by limiting overall functions and those performed remotely.

- Log privileged user activity and audit activity regularly.

In addition to setting a policy, strategy, and technical direction, an agency should evaluate the risk of all users to its resources by conducting a Digital Identity Risk Assessment. The DIRA process identifies the risk of user transactions and determines a minimum identity assurance, authenticator assurance, and federation assurance level outlined in NIST Special Publication 800-63-3.

Why Additional Controls?

Most attacks start by compromising lower-level accounts. An attacker can find an orphaned privileged account through network discovery and escalate their privileges to access applications, data, and compromise entire agency networks or data sets.

Metrics are an essential aspect of privileged user management which can help identify risks and efficiencies. The following metrics are modified from the GSA DevSecOps Guide.

Table 3: Example Privileged User Metrics

| Metric | Description |

|---|---|

| User provisioning lead time | The time between a request for a new user on the platform and the user being able to log in. |

| Access Control (AC) security control compliance | List and percentage of AC security controls satisfied via ICAM platform account management practices. |

| Privilege auditing frequency | The number of entitlement audits conducted in each period. |

| Administrator count | List and number of users with administrator-level privileges. |

| Secret rotation frequency | A set period to rotate a secret such as after every use or every 30 days. |

Step 2. Define and Identify

Agencies are responsible for managing all user privileges. Individuals entrusted with privileged accounts comprise an agency’s privileged user population.

Define a Privileged User

An agency’s privileged user population can include a range of accounts with elevated access. Given the broad-reaching nature of an organization’s privileged user population, an agency must understand the user roles, groups, and accounts that constitute its privileged user population. A privileged account can be owned by a person or a non-person entity. A non-person entity are those machine identities and digital workers that may execute code or perform automated processes that are created with an elevated privilege. Some common job titles or system accounts include:

- Job Titles

- Domain administrator

- Global administrator

- System administrator

- Help desk administrator

- Finance Manager

- System Accounts

- Linux/Unix Root

- Oracle SYS

- Cisco Enable

- Windows service accounts

- SSH (Secure Shell) keys

- Emergency or break-glass accounts

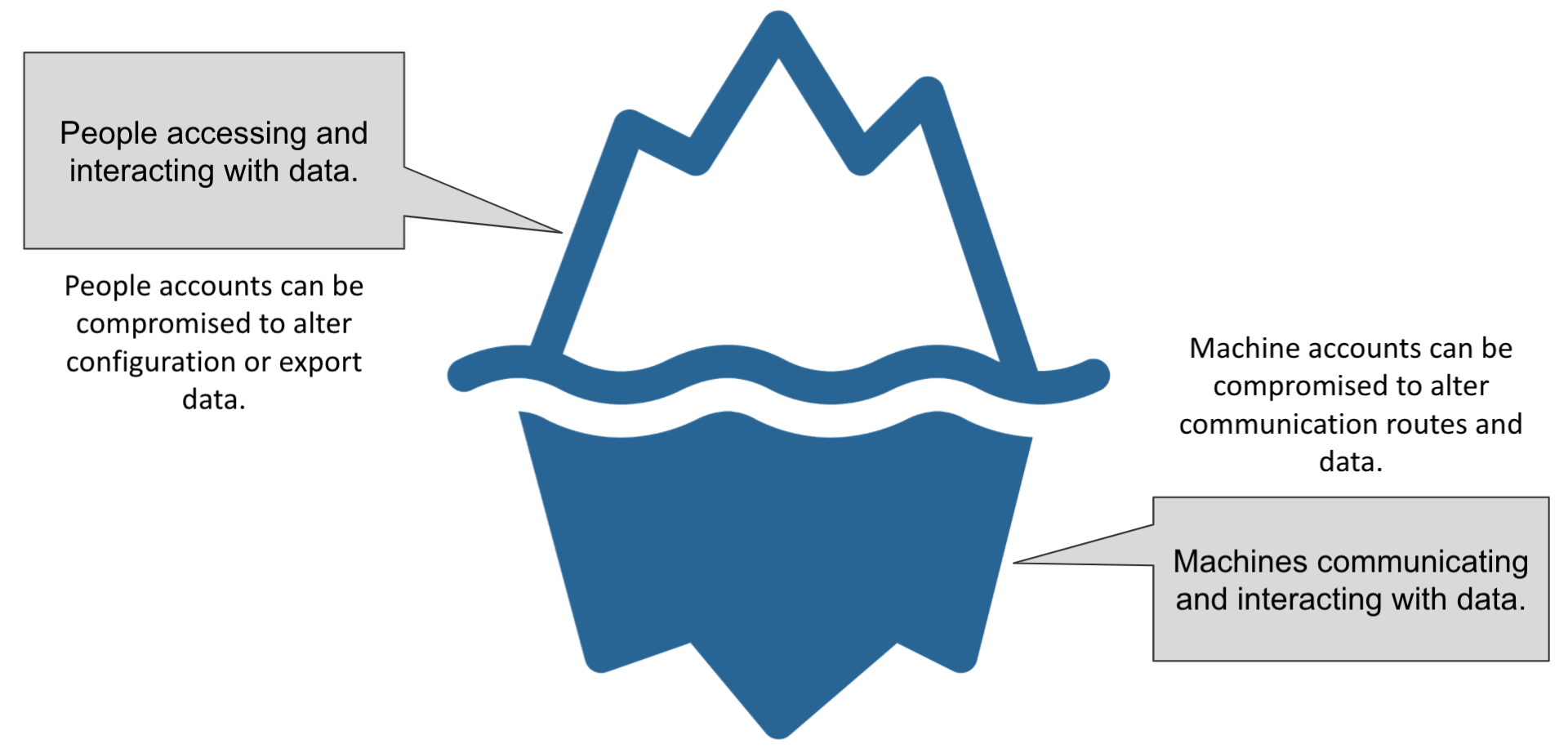

Figure 2: Privileged Users Can Be Either People or Non-Persons

Use Consistent Terms

The most common definition of a privileged user is a user who is authorized (and therefore, trusted) to perform security-relevant functions such as change configuration settings, running commands that require administrator access, or approving access requests. Some common characteristics of a privileged user include:

- Access that impacts the confidentiality, integrity, or availability of an application.

- Access to alter data or across multiple data sets.

- Ability to reset passwords.

- Ability to change access privileges.

- Ability to create accounts (especially other privileged accounts).

- Ability to start or stop processes in cloud-based tools.

Identify Privileged Accounts Across Platforms and Environments

Once the definition of a privileged user is established, an agency can identify its privileged users and resources by following this process:

- Identify and document mission-critical and sensitive services (most likely your high-value asset list) as a starting point. Every IT system has privileged users. An agency can also check system security plans to help identify privileged roles. Services can be further grouped by:

- Hardware

- Software

- Operating system

- Access type (externally accessible, internally accessible, or others)

- Physical and logical location (on-premises, cloud service provider, or others)

- Data sensitivity

- Identify and document IT staff roles, roles requiring separation of duties, trusted roles, and associated accounts that require elevated access to perform their role. The IT staff role may include identifying a specific cyber workforce position or role required to manage the system.

- Perform an automated analysis of permissions assigned versus those in use. The ongoing existence of unused but active permissions creates risk. The analysis can reveal unknown or unmanaged privileged user accounts originating by failure to disable

- the privileges of former employees

- default accounts created for new endpoints

- obsolete or abandoned accounts

- Perform an automated analysis to identify the existence of microservices, the applications that use them, and the associated user groups. Such an analysis provides context regarding microservice use as well as visibility into the potential threats they may create. The use environment might reflect a combination of privileged and nonprivileged users who are both internal and external to the organization. Use by one group might pose low risk whereas use by the other might create high risk warranting corrective action.

- Perform a privileged account discovery exercise to identify accounts that have elevated access. Accomplish discovery through an automated tool or directory analysis. Don’t be surprised if there are more privileged accounts than expected. Privileged account discovery intends to identify accounts that lack accountability. Account types may include group, orphaned, rogue, and default accounts that may go unnoticed or unmanaged. Discovery should consist of all environments, including Windows, Unix/Linux, database, applications, and cloud environments that encompass infrastructure, platform, and software as a service platforms and applications.

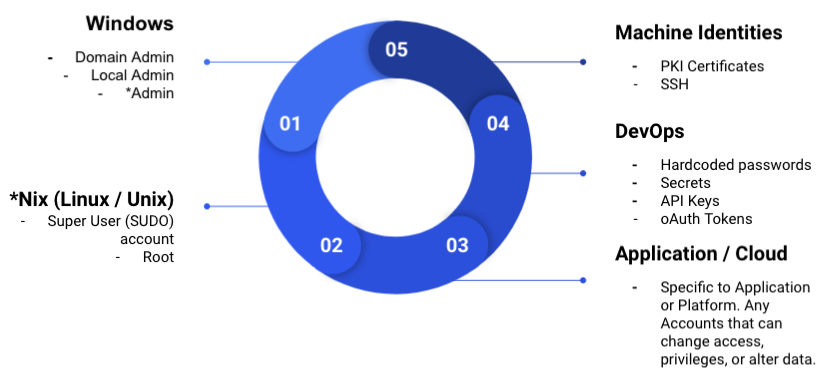

Figure 3: Location of Privileged Accounts

Protect Your DevOps Access

DevOps tools are a primary attack target. An attacker may extract privileged account credentials from one environment (i.e., DEV) and use them in subsequent environments (i.e., production) which is what happened in the SolarWinds Orion Network Management product compromise .

Step 3. Implement as an Enterprise ICAM Service

ICAM is the set of tools, policies, and systems an agency uses to provide the right individual with access to the right resources, at the right time, for the right reason in support of federal business objectives. In the context of privileged users, ICAM supports:

- Unifying IT services by consolidating various privileged access tools at an enterprise level. This may include consolidating not only enterprise IT, but also mission application access tools.

- Improving access control by tracking and monitoring privileged user accounts and access.

- Improving compliance by centralizing access requests, auditing, and reporting.

An agency should use existing processes, controls, programs, and available tools to manage its privileged user population and enterprise resources effectively. Please refer to Appendix C: NIST SP 800-53 Privileged User Overlay for a mapping of controls defined in SP 800-53. These controls are countermeasures for how an agency can reduce unwanted behavior by its privileged user population.

The DHS CDM Program provides a broad spectrum of tools that enable an agency to identify privileged user risk on an ongoing basis. It can also help prioritize these risks based on impact and allow agency security leadership to reduce the most significant privilege user challenges.

Privileged Identity Management

Identity management is how an agency collects, verifies, and manages attributes and entitlements for a privileged user. An agency should only grant entitlements that privileged users need to perform their assigned duties, thereby ensuring the least privilege as follows:

- Identify a cybersecurity workforce position that outlines the appropriate responsibilities and duties. Use the NIST Workforce Framework for Cybersecurity to identify suitable roles.

- Verify personnel security vetting and privileged user agreement by the Personnel Security Office and ICAM program manager on an initial and continuing basis. The security office verifies the existing background, suitability, or fitness checks are valid and adequate. An agency should implement a consistent approach when conducting these checks that ensures background checks commensurate with the privileged user’s level of risk as determined by an agency’s risk assessment (e.g., some trusted roles may require a security clearance in their position of trust). The user should also sign a privileged user agreement regularly. This agreement may also be called a Rules of Behavior or a privileged appointment letter. This agreement highlights the responsibilities of the privileged user and acceptable rules of behavior. See Appendix B: Privileged User Agreement for an agreement template.

- Conduct periodic training to ensure privileged users know their responsibilities and systems. An agency’s privileged user agreement may also include training requirements such as annual insider threat, security awareness, and tailored privileged user procedure training. Privilege users should receive initial and continuing training on the following topics:

- Privilege access security principles.

- Disaster recovery and business continuity procedures.

- Current and pending architecture changes, system characteristics, and hardware and software components.

- Enforce least privilege to only allow privileged users access to what is needed to perform their duty. If possible, implement just-in-time provisioning or account password check-out capabilities. Additional actions may include creating custom administrator accounts scoped for the role, like an application administrator versus a global administrator, and role rotation.

- Manage administrator lifecycle by implementing and following lifecycle management practices in the Identity Lifecycle Management playbook.

- Integrate with an agency identity directory to reduce the potential of creating an orphaned privileged identity. In DHS CDM, this directory is called a master user record.

- Provision access when needed.

- Conduct access reviews every 30 days or less based on a risk determination and modify privileges as needed.

- De-provision users within 24 hours or less when access is no longer needed, their role changes, or users leave the organization. These de-provisioning activities should be integrated with ICAM processes and automated to the highest extent possible.

Identity Assurance Level 3

Privileged users most likely require the highest level of identity proofing. The Personal Identity Verification (PIV) vetting process is comparable to Identity Assurance Level 3 (IAL3).

Privileged Credential Management

Credential management is how an agency issues, manages, and revokes privileged credentials. Agencies issue unique Authenticator** Assurance Level 3 credentials** for each privileged user. Credentials may include a PIV card or other phishing-resistant multi-factor cryptographic hardware authenticator identified in NIST Special Publication 800-63-3B.

Authenticator Assurance Level 3

Privileged users require the highest-level credential. A PIV card may not work in every use case. Instead, consider the best Authenticator Assurance Level 3 credential, which may include Fast Identity Online 2 (FIDO2) authenticators, for each type of access use case.

An agency may use a privileged access gateway or management solution to enable a PIV card or other phishing-resistant authenticator for enterprise resources that do not support PIV. A privileged access management solution is an intermediary between a privileged user and an enterprise resource such as a management console, database, or command-line interface. It may provide additional capabilities such as password vaulting, key vaulting, keystroke logging, session recording, account checkout, and just-in-time provisioning.

Privileged Access Management

Access management is how an agency authenticates privileged users and authorizes access to protected services.

- Enforce Multi-factor Authentication (MFA) for all administrator access. This may include a combination of phishing-resistant multi-factor authentication factors as outlined in NIST Special Publication 800-63.

- Follow OMB Memo 22-09 guidance which states Privileged Access Management (PAM) solutions that provide ephemeral single-factor credentials for human access to a system should not be used as a general purpose substitute for multi-factor authentication, or for routine single-sign-on access to legacy systems in place of needed modernization of those systems.

- Privilege access requests are completed regularly and ongoing. The ongoing activity may be called an access review or certification. Access reviews may be paper-based but plan to automate this process through a workflow or identity entitlement tool.

- Monitor privileged user activity via activity logging and regular log reviews. Additional controls may include keystroke logging and session recording based on risk assessment. Consider user behavior automated monitoring outlined in insider threat programs. Because of the heightened risk, an agency can hold privileged users to a higher monitoring standard than standard users.

- Use dedicated workstations with limited applications and internet connectivity. This limits the potential risk of remote access exploitation and malware. A dedicated workstation may be called a privileged access workstation, a jump box, or bastion host.

Preventative and Detective Measures

Preventative measures proactively stop inappropriate behavior through background investigations, training, rules of behavior, privileged access workstation, and other mechanisms. Detective measures identify suspicious activities such as audit logs, keystroke logging, access logs, and account checkout. Agencies should use a combination to decrease privilege user risk.

Step 4. Prioritize and Execute

This step explains the technical capabilities necessary to accomplish privileged user management goals and objectives. An agency should complete the following steps:

- Create privileged user management with proper governance and leadership.

- Scan and inventory systems to focus on those with a Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS) categorization of high for confidentiality or integrity. Consider the risk impact of non-high connected systems such as an Agency Identity Directory compromise.

- Leverage existing processes, controls, programs, and available tools to manage the privileged user population and enterprise resources effectively. Use capabilities from other ICAM services, such as Identity Governance and Administration (IGA), to bring privileged users into the context of a user in the organization.

Prioritize by Risk

Plan your technical coverage from the highest risk first. Systems that can change network configuration or access controls have "infrastructure impact" and are the most significant concern. Once your agency is comfortable with the process, consider expanding privileged user management to more systems and greater control.

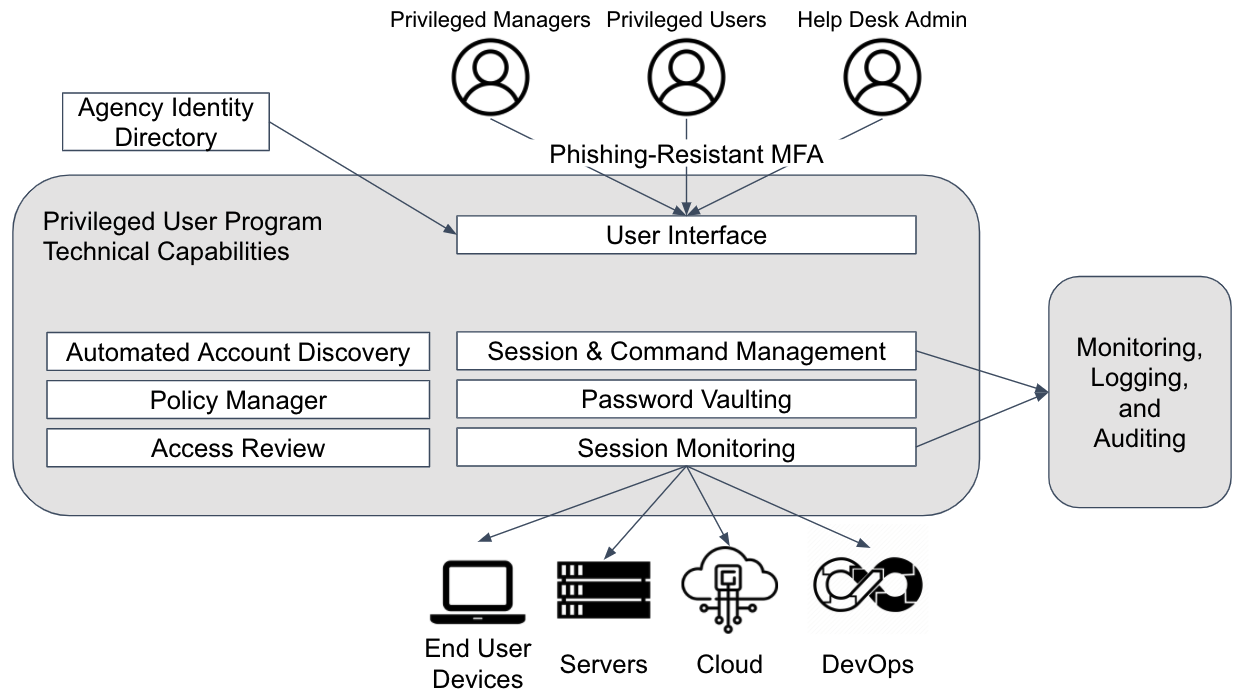

Figure 4: Privileged Identity Capabilities

Privileged Identity Baseline Capabilities

Understand the data flows and access types when designing the technical components of privileged user management. This section combines best practices from NIST Special Publication 1800-18 Privileged Access Management and the DHS Continuous Diagnostics and Mitigation PRIV function. The minimum capability baseline should consist of the three elements below.

-

An account discovery identifies current and newly created privileged accounts. Look for accounts on these systems that can provide lateral movement or execute changes to the privileges or other accounts. Advanced discovery can identify when privileged access is inherited rather than directly entitled.

-

The policy manager establishes access control policies, including a password complexity and rotation policy, MFA policy, session timeout, number of access attempts, and session requirements that only allow specific protocols. This may be part of a privileged access management tool or a separate type of privileged access (e.g., Windows Operating System manager for remote desktop protocol).

-

An access review capability that requires account reviews regularly, such as every 30 days. Conducting access reviews ensures the privileged user only has access to accounts for as long as they are needed.

Privileged Identity Advanced Capabilities

An agency should consider using a privileged access management (PAM) tool that centralizes technical capabilities with advanced features for higher-risk systems when baseline capabilities do not mitigate the risk sufficiently. Some cloud applications may have these advanced features as part of existing licensing. Review capabilities available under current tools and licensing before evaluating new solutions. A privileged account or access management tool is vital to protect high-value assets that are difficult or infeasible to modernize. A PAM tool can implement necessary security controls such as multi-factor authentication, fine-grained access control, auditing and reporting, and other capabilities. In addition to centralizing capabilities and enhancing the security of legacy infrastructure, the advanced capabilities include three core elements below:

-

Session & command management enforces the access control settings in the policy manager. This may cover multiple protocols such as remote desktop protocol, secure shell, azure command line, or others.

-

Password vaulting stores and rotates passwords managed by a PAM tool.

- Session monitoring records each privileged session. This can help with monitoring, logging, and auditing or be used for training purposes. A session recording can include an actual live screen recording or keystroke recording.

- Advanced Automated Account Discovery provides immediate control over rogue accounts and devices as soon as they are created or discovered. This feature is key to mitigate a malicious Active Directory ticket-granting activity such as “Kerberoasting” or a Golden Ticket attack.

Conclusion

Privileged users are at the core of protecting federal information technology assets. Government employees and contractors need elevated access to perform necessary administrative and security functions however, this creates an inherent risk of insider threat or account compromise. Agencies can reduce privileged user risk by implementing and maintaining privileged user management that encompasses both human and non-human users. It is recommended to integrate the management of your privileged users with your agency ICAM tools and provide enterprise-wide services to all agency mission applications. Prioritize privilege identity control over highest risk systems and execute on the requirements to keep federal data secure.

Appendix A: Reference Documentation

The following documentation references help inform the development and direction of a privileged user program.

- National Insider Threat Policy, November 2012

- This policy sets two priorities to strengthen the protection and safeguarding of classified information. It also references Executive Order 13587 (October 2011) as the primary authority to establish insider threat programs.

- Create the Insider Threat Task Force.

- Set the minimum standards for Executive Branch Insider Threat programs.

- This policy sets two priorities to strengthen the protection and safeguarding of classified information. It also references Executive Order 13587 (October 2011) as the primary authority to establish insider threat programs.

- National Strategy for Information Sharing and Safeguarding, December 2012

- This strategy aims to strike the proper balance between sharing information with those who need it to keep our country safe and safeguarding it from those who would do us harm. As an agency works to extend its ICAM implementations across security domains, it is important to consider Goal #4 and Priority Objective #4 in relation to managing privileged users.

- Goal #4 focuses on identifying, preventing, and mitigating insider threat across all domains.

- Priority Objective #4 extends and implements the FICAM roadmap across all security domains. Note: The FICAM roadmap is superseded by the FICAM architecture and accompanying playbooks.

- This strategy aims to strike the proper balance between sharing information with those who need it to keep our country safe and safeguarding it from those who would do us harm. As an agency works to extend its ICAM implementations across security domains, it is important to consider Goal #4 and Priority Objective #4 in relation to managing privileged users.

- National Insider Threat Task Force (NITTF)

- The primary mission of the NITTF is to develop a government-wide insider threat program to deter, detect, and mitigate insider threats, including safeguarding classified information from exploitation, compromise, or other unauthorized disclosure, and accounting for risk levels as well as any individual agency needs, missions, and systems.

- OMB Memo 17-09 - Management of Federal High Value Assets

- General guidance for the planning, identification, categorization, prioritization, reporting, assessment, and remediation of federal HVAs.

- NIST Special Publication 1800-18 - Privileged Account Management for the Financial Services Sector

- While this special publication is focused on the financial services industry, it also contains agnostic implementation best practices.

- NIST Interagency Report 7966 - Security of Interactive and Automated Access Management Using Secure Shell (SSH)

- This publication assists organizations in understanding the basics of SSH interactive and automated access management in an enterprise, focusing on the management of SSH user keys.

- Federal Identity, Credentials, and Access Management (FICAM) Architecture - Access Management

- The FICAM Architecture is a framework for an agency to use in ICAM program and solution roadmap planning. Privileged Access Management is identified as a distinct service within the access management portion of the ICAM services framework.

- Common Sense Guide to Mitigating Insider Threats (6th Edition), February 2019

- The Software Engineering Institute at Carnegie Mellon University’s Insider Threat Center released the Common Sense Guide to provide the federal government and industry with recommendations on insider threat mitigation, based on a database of more than 700 cases. This work was sponsored by the Department of Homeland Security, Office of Cybersecurity and Communications and the U.S. Secret Service. The Common Sense Guide presents readers with 19 best practices to mitigate insider threats.

Appendix B: Privileged User Agreement

An agency can tailor this template to help meet mission goals and business needs to support privileged user access for logical and physical resources. An agency should obtain and retain a digitally signed copy of such instruction and ensure that privileged user access to the identified protected resource is prohibited without a signed acknowledgment of system-specific rules and a signed acknowledgment of said instruction.

[AGENCY OR PROGRAM NAME] Privileged User Agreement

Version 1.0

Last Updated: August 10, 2021

I am being granted elevated access to [AGENCY or PROGRAM NAME] controlled systems and facilities and am responsible for all actions taken under my accounts. I agree to the following:

- I will only use my elevated privileges to perform authorized tasks or mission-related functions on systems I am authorized to access.

- I will not use my elevated privileges to perform routine tasks that do not require elevated access.

- I will obtain and maintain required certifications and trainings according to [AGENCY OR PROGRAM POLICY], including but not limited to specialized role-based security and privacy training.

- I understand the need to safeguard all credentials at the level appropriate to the data they protect.

- I will not share passwords, accounts, or other credentials with unwanted personnel.

- I will only add and remove users to the [ADMINISTRATOR GROUPS] group after receiving approval/direction from the [AGENCY OR PROGRAM POINT OF CONTACT].

- I will not install, modify, or remove any hardware or software without written approval from the [AGENCY OR PROGRAM POINT OF CONTACT].

- I will not knowingly introduce any viruses, malicious/unwanted code, malware, or Trojan horse programs into [AGENCY OR PROGRAM NAME] systems.

- I will not attempt to hack the network or connected information systems to gain access to data or agency assets which I am authorized to access. I will not use sensitive information for anything other than the purpose for which it has been authorized.

- I will contact the [AGENCY OR PROGRAM POINT OF CONTACT] if I require clarification of my roles or responsibilities.

I understand that failure to comply with the above requirements may result in disciplinary action, including termination of employment; removal or disbarment from work on federal contracts or projects; revocation of access to federal information, information systems, and/or facilities; criminal penalties; and/or imprisonment. I also understand that violation of certain laws, such as the Privacy Act of 1974, copyright law, and 18 USC 2071 can result in monetary fines and criminal charges that may result in imprisonment.

Printed Name:

Date:

Digital Signature (preferred):

Appendix C: NIST SP 800-53 Privileged User Overlay

In seeking to implement cohesive, integrated privileged user practices, an agency should consider existing controls and practices that can assist in safeguarding the enterprise’s protected resources from privileged compromise. This section provides an analysis of countermeasures for privileged user compromise by leveraging NIST SP 800- 53 security controls.

For each countermeasure, an accompanying explanation provides guidance on how the associated control relates to privileged users to assist an agency defend relevant protected resources. The controls are organized into the control families as listed in SP 800-53.

| Countermeasure | Control | Explanation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access Control | |||||

| Dynamic Privilege Management | AC-2(6) |

|

|||

| Privileged User Accounts | AC-2(7) |

|

|||

| Separation of Duties | AC-5 |

|

|||

| Least Privilege | AC-6 |

|

|||

| Remote Access | AC-17 |

|

|||

| Audit and Accountability | |||||

| Event Logging | AU-2 | An event is an observable occurrence in a system. The types of events that require logging are those events that are significant and relevant to the security of systems and the privacy of individuals. Event logging also supports specific monitoring and auditing needs. Event types include password changes, failed logons or failed accesses related to systems, security or privacy attribute changes, administrative privilege usage, PIV credential usage, data action changes, query parameters, or external credential usage. In determining the set of event types that require logging, organizations consider the monitoring and auditing appropriate for each of the controls to be implemented. For completeness, event logging includes all protocols that are operational and supported by the system. To balance monitoring and auditing requirements with other system needs, event logging requires identifying the subset of event types that are logged at a given point in time. For example, organizations may determine that systems need the capability to log every file access successful and unsuccessful, but not activate that capability except for specific circumstances due to the potential burden on system performance. The types of events that organizations desire to be logged may change. Reviewing and updating the set of logged events is necessary to help ensure that the events remain relevant and continue to support the needs of the organization. Organizations consider how the types of logging events can reveal information about individuals that may give rise to privacy risk and how best to mitigate such risks. For example, there is the potential to reveal personally identifiable information in the audit trail, especially if the logging event is based on patterns or time of usage. Event logging requirements, including the need to log specific event types, may be referenced in other controls and control enhancements. These include AC-2(4), AC-3(10), AC-6(9), AC-17(1), CM-3f, CM-5(1), IA-3(3.b), MA-4(1), MP-4(2), PE-3, PM-21, PT-7, RA-8, SC-7(9), SC-7(15), SI-3(8), SI-4(22), SI-7(8), and SI-10(1). Organizations include event types that are required by applicable laws, executive orders, directives, policies, regulations, standards, and guidelines. Audit records can be generated at various levels, including at the packet level as information traverses the network. Selecting the appropriate level of event logging is an important part of a monitoring and auditing capability and can identify the root causes of problems. When defining event types, organizations consider the logging necessary to cover related event types, such as the steps in distributed, transaction-based processes and the actions that occur in service-oriented architectures. | |||

| Content of audit records | AU-3 | Audit record content that may be necessary to support the auditing function includes event descriptions (item a), time stamps (item b), source and destination addresses (item c), user or process identifiers (items d and f), success or fail indications (item e), and filenames involved (items a, c, e, and f) . Event outcomes include indicators of event success or failure and event-specific results, such as the system security and privacy posture after the event occurred. Organizations consider how audit records can reveal information about individuals that may give rise to privacy risks and how best to mitigate such risks. For example, there is the potential to reveal personally identifiable information in the audit trail, especially if the trail records inputs or is based on patterns or time of usage. | |||

| Audit record review, analysis, and reporting | AU-6 | Audit record review, analysis, and reporting covers information security- and privacy-related logging performed by organizations, including logging that results from the monitoring of account usage, remote access, wireless connectivity, mobile device connection, configuration settings, system component inventory, use of maintenance tools and non-local maintenance, physical access, temperature and humidity, equipment delivery and removal, communications at system interfaces, and use of mobile code or Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP). Findings can be reported to organizational entities that include the incident response team, help desk, and security or privacy offices. If organizations are prohibited from reviewing and analyzing audit records or unable to conduct such activities, the review or analysis may be carried out by other organizations granted such authority. The frequency, scope, and/or depth of the audit record review, analysis, and reporting may be adjusted to meet organizational needs based on new information received | |||

| Protection of audit information | AU-9 | Audit information includes all information needed to successfully audit system activity, such as audit records, audit log settings, audit reports, and personally identifiable information. Audit logging tools are those programs and devices used to conduct system audit and logging activities. Protection of audit information focuses on technical protection and limits the ability to access and execute audit logging tools to authorized individuals. Physical protection of audit information is addressed by both media protection controls and physical and environmental protection controls. | |||

| Awareness and Training | |||||

| Literacy training and awareness | AT-2 |

|

|||

| Configuration Management | |||||

| Develop and configuration baselines for information systems | CM-2 | By establishing baseline configurations for information systems and their components, an agency can help prevent privileged users from incorrectly assuming a role in altering the information system. Even though baseline configurations must change over time to reflect the current enterprise architecture, this countermeasure centralizes information about the information system components and network topology. This centralization can delineate parameters around the role of privileged users to provide guidance on configurations management so the system performs as intended. Documenting the configurations of all assets allows the agency to audit for anomalies, possible signs of insider activity from the privileged users in relevant roles. | |||

| Change configuration baselines in a secure, systematic manner | CM-3 | Unwanted changes to configuration baselines can create severe vulnerabilities for information system components. An agency should use Configuration Change Boards to approve major changes to the baseline configuration to reflect the current enterprise architecture. Since this is a privileged function, changes should be conducted by a group of people to maintain accountability and avoid abuse by one individual. An agency should have a clearly defined system of proposal, justification, implementation, testing, review, and disposition for system upgrades and modifications. | |||

| Appropriately restrict privileged users ability to modify information systems | CM-5 | An agency should limit the privileges for modifying the hardware and software or firmware components of an information system because these changes have such a significant impact on the security of protected resources. The individuals who perform these duties are privileged users because of these changes require elevated access. An agency should maintain access records to confirm these privileged users appropriately carry out their duties. In addition, an agency can institute processes like dual authorization and code authentication for installed components to restrict the privileged users ability to misuse or abuse their trusted position of modifying the information system. | |||

| Establish, document, and monitor configuration settings | CM-6 | Configuration settings are the parameters that can be changed in the hardware, software, or firmware components of the system that affect the security and privacy posture or functionality of the system. Information technology products for which configuration settings can be defined include mainframe computers, servers, workstations, operating systems, mobile devices, input/output devices, protocols, and applications. Parameters that impact the security posture of systems include registry settings; account, file, or directory permission settings; and settings for functions, protocols, ports, services, and remote connections. Privacy parameters are parameters impacting the privacy posture of systems, including the parameters required to satisfy other privacy controls. Privacy parameters include settings for access controls, data processing preferences, and processing and retention permissions. Organizations establish organization-wide configuration settings and subsequently derive specific configuration settings for systems. The established settings become part of the configuration baseline for the system. Common secure configurations (also known as security configuration checklists, lockdown and hardening guides, and security reference guides) provide recognized, standardized, and established benchmarks that stipulate secure configuration settings for information technology products and platforms as well as instructions for configuring those products or platforms to meet operational requirements. Common secure configurations can be developed by a variety of organizations, including information technology product developers, manufacturers, vendors, federal agencies, consortia, academia, industry, and other organizations in the public and private sectors. Implementation of a common secure configuration may be mandated at the organization level, mission and business process level, system level, or at a higher level, including by a regulatory agency. Common secure configurations include the United States Government Configuration Baseline [USGCB] and security technical implementation guides (STIGs), which affect the implementation of CM-6 and other controls such as AC-19 and CM-7. The Security Content Automation Protocol (SCAP) and the defined standards within the protocol provide an effective method to uniquely identify, track, and control configuration settings | |||

| Ensure information system components are fitted for least functionality | CM-7 | By limiting functionality of information system components to only those that are necessary, an agency can protect the enterprise against unwanted data exfiltration by employees. For example, physical or logical ports, fire-sharing capabilities, or instant messaging can be disabled when the component does not require its use or is not necessary to support essential organizational missions, functions, or operations. An agency can employ blacklisting (list of unwanted software) or whitelisting (list of authorized software) to further inhibit unwanted actions. Implementing these controls allows the agency an extra layer of protection against abuse or misuse of its systems by privileged users, as well as standards users. | |||

| Create a centralized inventory of information system components | CM-8 | System components are discrete, identifiable information technology assets that include hardware, software, and firmware. Organizations may choose to implement centralized system component inventories that include components from all organizational systems. In such situations, organizations ensure that the inventories include system-specific information required for component accountability. The information necessary for effective accountability of system components includes the system name, software owners, software version numbers, hardware inventory specifications, software license information, and for networked components, the machine names and network addresses across all implemented protocols (e.g., IPv4, IPv6). Inventory specifications include date of receipt, cost, model, serial number, manufacturer, supplier information, component type, and physical location. Preventing duplicate accounting of system components addresses the lack of accountability that occurs when component ownership and system association is not known, especially in large or complex connected systems. Effective prevention of duplicate accounting of system components necessitates use of a unique identifier for each component. For software inventory, centrally managed software that is accessed via other systems is addressed as a component of the system on which it is installed and managed. Software installed on multiple organizational systems and managed at the system level is addressed for each individual system and may appear more than once in a centralized component inventory, necessitating a system association for each software instance in the centralized inventory to avoid duplicate accounting of components. Scanning systems implementing multiple network protocols (e.g., IPv4 and IPv6) can result in duplicate components being identified in different address spaces. The implementation of CM-8(7) can help to eliminate duplicate accounting of components. | |||

| Contingency Planning | |||||

| Explanation Relevant Protected Resources Use an alternate storage site | CP-6 | An alternative storage site for information system backup information, geographically distinct from the primary site, increases complexity for a malicious privileged user to purposefully inflict damage on an agency. By housing information in two or more distinct places, an individual would have to destroy or modify the information housed in both sites to permanently cripple the information systems backup capabilities. An agency should carefully monitor and implement stringent processes for the privileged users who have access to both sites content and data. | |||

| System Backup | CP-9 | System-level information includes system state information, operating system software, middleware, application software, and licenses. User-level information includes information other than system-level information. Mechanisms employed to protect the integrity of system backups include digital signatures and cryptographic hashes. Protection of system backup information while in transit is addressed by MP-5 and SC-8. System backups reflect the requirements in contingency plans as well as other organizational requirements for backing up information. Organizations may be subject to laws, executive orders, directives, regulations, or policies with requirements regarding specific categories of information (e.g., personal health information). Organizational personnel consult with the senior agency official for privacy and legal counsel regarding such requirements. | |||

| System recovery and reconstitution | CP-10 | Recovery is executing contingency plan activities to restore organizational mission and business functions. Reconstitution takes place following recovery and includes activities for returning systems to fully operational states. Recovery and reconstitution operations reflect mission and business priorities; recovery point, recovery time, and reconstitution objectives; and organizational metrics consistent with contingency plan requirements. Reconstitution includes the deactivation of interim system capabilities that may have been needed during recovery operations. Reconstitution also includes assessments of fully restored system capabilities, reestablishment of continuous monitoring activities, system reauthorization (if required), and activities to prepare the system and organization for future disruptions, breaches, compromises, or failures. Recovery and reconstitution capabilities can include automated mechanisms and manual procedures. Organizations establish recovery time and recovery point objectives as part of contingency planning. | |||

| Identification and Authentication | |||||

| Require the use of PIV credential or Multi-Factor Authentication | IA-2 | All agencies should be leveraging PIV card credentials for employee access to physical and logical resources per HSPD-12 and alignment with the ICAM target state. Information systems need to uniquely identify and authenticate its users to maintain security. However, to manage privileged users, an agency could require an additional layer of authentication, in addition to the standard multifactor authentication used for local and network access. Namely, an agency should consider implementing unique identification of individuals using shared privileged accounts and detailed accountability of individual privileged user activity. | |||

| Incident Response | |||||

| Develop and implement incident handling capability commensurate to inherent risk of privileged user abuse | IR-4 | Organizations recognize that incident response capabilities are dependent on the capabilities of organizational systems and the mission and business processes being supported by those systems. Organizations consider incident response as part of the definition, design, and development of mission and business processes and systems. Incident-related information can be obtained from a variety of sources, including audit monitoring, physical access monitoring, and network monitoring; user or administrator reports; and reported supply chain events. An effective incident handling capability includes coordination among many organizational entities (e.g., mission or business owners, system owners, authorizing officials, human resources offices, physical security offices, personnel security offices, legal departments, risk executive [function], operations personnel, procurement offices). Suspected security incidents include the receipt of suspicious email communications that can contain malicious code. Suspected supply chain incidents include the insertion of counterfeit hardware or malicious code into organizational systems or system components. For federal agencies, an incident that involves personally identifiable information is considered a breach. A breach results in unauthorized disclosure, the loss of control, unauthorized acquisition, compromise, or a similar occurrence where a person other than an authorized user accesses or potentially accesses personally identifiable information or an authorized user accesses or potentially accesses such information for other than authorized purposes. | |||

| Information spillage response plan | IR-9 | Information spillage refers to instances where information is placed on systems that are not authorized to process such information. Information spills occur when information that is thought to be a certain classification or impact level is transmitted to a system and subsequently is determined to be of a higher classification or impact level. At that point, corrective action is required. The nature of the response is based on the classification or impact level of the spilled information, the security capabilities of the system, the specific nature of the contaminated storage media, and the access authorizations of individuals with authorized access to the contaminated system. The methods used to communicate information about the spill after the fact do not involve methods directly associated with the actual spill to minimize the risk of further spreading the contamination before such contamination is isolated and eradicate. | |||

| Literacy and Training | |||||

| Role-based training | AT-3 | Organizations determine the content of training based on the assigned roles and responsibilities of individuals as well as the security and privacy requirements of organizations and the systems to which personnel have authorized access, including technical training specifically tailored for assigned duties. Roles that may require role-based training include senior leaders or management officials (e.g., head of agency/chief executive officer, chief information officer, senior accountable official for risk management, senior agency information security officer, senior agency official for privacy), system owners; authorizing officials; system security officers; privacy officers; acquisition and procurement officials; enterprise architects; systems engineers; software developers; systems security engineers; privacy engineers; system, network, and database administrators; auditors; personnel conducting configuration management activities; personnel performing verification and validation activities; personnel with access to system-level software; control assessors; personnel with contingency planning and incident response duties; personnel with privacy management responsibilities; and personnel with access to personally identifiable information. Comprehensive role-based training addresses management, operational, and technical roles and responsibilities covering physical, personnel, and technical controls. Role-based training also includes policies, procedures, tools, methods, and artifacts for the security and privacy roles defined. Organizations provide the training necessary for individuals to fulfill their responsibilities related to operations and supply chain risk management within the context of organizational security and privacy programs. Role-based training also applies to contractors who provide Services to federal agencies. Types of training include web-based and computer-based training, classroom-style training, and hands-on training (including micro-training). Updating role-based training on a regular basis helps to ensure that the content remains relevant and effective. Events that may precipitate an update to role-based training content include, but are not limited to, assessment or audit findings, security incidents or breaches, or changes in applicable laws, executive orders, directives, regulations, policies, standards, and guidelines. | |||

| Maintenance | |||||

| Exercise strict supervision and access procedures for maintenance personnel | MA-5 | Maintenance personnel can be considered privileged users due to their trusted position with information systems and the extraordinary access granted to them. Software and hardware require maintenance often on short notice. As such, an agency might have to bring in individuals not previously identified as authorized maintenance personnel. An agency should maintain a list of individuals authorized to carry out this type of maintenance. For those individuals who are not escorted throughout the facility, the agency should verify these maintenance personnel have the necessary and required authorizations. For those individuals who do not possess required authorizations and must be escorted, supervisory personnel must possess the technical expertise to oversee the maintenance activities. This measure can detect or deter harmful activity on the part of the maintenance personnel. Temporary credentials (e.g., visitor badge, password) granted to maintenance personnel must be terminated as soon as maintenance concludes. | |||

| Media Protection | |||||

| Restrict media use for privileged users | MP-7 | System media includes both digital and non-digital media. Digital media includes diskettes, magnetic tapes, flash drives, compact discs, digital versatile discs, and removable hard disk drives. Non-digital media includes paper and microfilm. Media use protections also apply to mobile devices with information storage capabilities. In contrast to MP-2, which restricts user access to media, MP-7 restricts the use of certain types of media on systems, for example, restricting or prohibiting the use of flash drives or external hard disk drives. Organizations use technical and nontechnical controls to restrict the use of system media. Organizations may restrict the use of portable storage devices, for example, by using physical cages on workstations to prohibit access to certain external ports or disabling or removing the ability to insert, read, or write to such devices. Organizations may also limit the use of portable storage devices to only approved devices, including devices provided by the organization, devices provided by other approved organizations, and devices that are not personally owned. Finally, organizations may restrict the use of portable storage devices based on the type of device, such as by prohibiting the use of writeable, portable storage devices and implementing this restriction by disabling or removing the capability to write to such devices. Requiring identifiable owners for storage devices reduces the risk of using such devices by allowing organizations to assign responsibility for addressing known vulnerabilities in the devices. | |||

| Personnel Security | |||||

| Develop, document, and disseminate clear policies on personnel security | PS-1 | An agency should monitor employees with elevated access beginning with the hiring process. In managing components of a workforce, clearly documented personnel policies are important. The privileged user should be aware of all facets of the agency duties and abilities to determine access rights for, adjust responsibilities of, and monitor its privileged user population. This not only provides legal protection for the agency, but the ramifications of misuse or abuse serve as a deterrent to unwanted behavior by privileged users. | |||

| Position risk designation | PS-2 | Position risk designations reflect Office of Personnel Management (OPM) policy and guidance. Proper position designation is the foundation of an effective and consistent suitability and personnel security program. The Position Designation System (PDS) assesses the duties and responsibilities of a position to determine the degree of potential damage to the efficiency or integrity of the service due to misconduct of an incumbent of a position and establishes the risk level of that position. The PDS assessment also determines if the duties and responsibilities of the position present the potential for position incumbents to bring about a material adverse effect on national security and the degree of that potential effect, which establishes the sensitivity level of a position. The results of the assessment determine what level of investigation is conducted for a position. Risk designations can guide and inform the types of authorizations that individuals receive when accessing organizational information and information systems. Position screening criteria include explicit information security role appointment requirements. Parts 1400 and 731 of Title 5, Code of Federal Regulations, establish the requirements for organizations to evaluate relevant covered positions for a position sensitivity and position risk designation commensurate with the duties and responsibilities of those positions. | |||

| Screen privileged users based on type of risk designation | PS-3 | Personnel screening criteria hinge on an individual’s risk designation. However, an agency is free to define different screening conditions and frequencies based on the information processed, stored, or transmitted by information systems. If a user has elevated access to manage a critical information system, an agency can enforce stricter screening procedures. Screening involves coordination with personnel security (e.g., background investigation status, reinvestigation). | |||

| Follow secure and comprehensive personnel termination procedures | PS-4 | Termination procedures are especially important if the departing employee had been granted elevated access, because a disgruntled, privileged user poses an even greater risk to an agency protected resources than a disgruntled user with standard access. When terminating an employee, the agency should:

|

|||

| Continuously evaluate authorizations granted to the privileged user population | PS-5 | If a privileged user transfers to a different department within the agency, the individual might be granted additional physical and logical access associated with new job duties. Failing to terminate privileges from an individual’s prior assignment risks inadvertently empowering the privileged user with a greater collection of authorizations than is explicitly needed. Maintaining access authorizations in line with Human Resources records is critical to mitigating the threat a privileged user can pose to an agency. An agency should conduct continuous evaluation on its privileged users to confirm these individuals have an ongoing operational need for their privileges. | |||

| Confirm employees sign access agreements prior to granting them access | PS-6 | Prior to granting access, an agency should develop, distribute, and document signed access agreements for employees who use agency information systems. Through non-disclosure agreements, acceptable use agreements, and rules of behavior agreements an agency can hold its employees accountable. An agency should consider tailoring these agreements to privileged users where necessary, as the nature of their access is very different than that of standard users. | |||

| Institute a formal personnel sanctions process | PS-8 | Access agreements should explain the ramifications of employees violating the terms of agreement, including any personnel sanctions involved. By instituting a formal sanctions process the agency can protect its resources from privileged users who exhibit tendencies towards unwanted behavior. | |||

| Physical and Environmental Protection | |||||

| Monitor physical access of privileged users | PE-6 | Monitoring physical access is fundamental to conducting continuous evaluation activities, which determine on an ongoing basis that all users, including privileged users, are granted the proper access to the protected resources their job roles require. Continuous evaluation is a central component to privileged user management, as the scope of these individuals elevated access should be constantly validated because of the inherent risk of harm to protected resources. If an organization’s physical access monitoring detects suspicious activity, like access for unusual lengths of time, the user could present an insider threat. Robust physical monitoring capabilities serve as a deterrent to malicious insider activity. | |||

| Planning | |||||

| Resources Rules of behavior | PL-4 | Rules of behavior represent a type of access agreement for organizational users. Other types of access agreements include nondisclosure agreements, conflict-of-interest agreements, and acceptable use agreements (see PS-6). Organizations consider rules of behavior based on individual user roles and responsibilities and differentiate between rules that apply to privileged users and rules that apply to general users. Establishing rules of behavior for some types of non-organizational users, including individuals who receive information from federal systems, is often not feasible given the large number of such users and the limited nature of their interactions with the systems. Rules of behavior for organizational and non-organizational users can also be established in AC-8. The related controls section provides a list of controls that are relevant to organizational rules of behavior. PL-4b, the documented acknowledgment portion of the control, may be satisfied by the literacy training and awareness and role-based training programs conducted by organizations if such training includes rules of behavior. Documented acknowledgments for rules of behavior include electronic or physical signatures and electronic agreement check boxes or radio buttons. | |||

| Risk Assessment | |||||

| Risk Assessment | RA-3 |

|

|||

| Security Assessment and Authorization | |||||

| Information Exchange | CA-3 | System information exchange requirements apply to information exchanges between two or more systems. System information exchanges include connections via leased lines or virtual private networks, connections to internet service providers, database sharing or exchanges of database transaction information, connections and exchanges with cloud services, exchanges via web-based services, or exchanges of files via file transfer protocols, network protocols (e.g., IPv4, IPv6), email, or other organization-to-organization communications. Organizations consider the risk related to new or increased threats that may be introduced when systems exchange information with other systems that may have different security and privacy requirements and controls. This includes systems within the same organization and systems that are external to the organization. A joint authorization of the systems exchanging information, as described in CA-6(1) or CA-6(2), may help to communicate and reduce risk. Authorizing officials determine the risk associated with system information exchange and the controls needed for appropriate risk mitigation. The types of agreements selected are based on factors such as the impact level of the information being exchanged, the relationship between the organizations exchanging information (e.g., government to government, government to business, business to business, government or business to service provider, government or business to individual), or the level of access to the organizational system by users of the other system. If systems that exchange information have the same authorizing official, organizations need not develop agreements. Instead, the interface characteristics between the systems (e.g., how the information is being exchanged. how the information is protected) are described in the respective security and privacy plans. If the systems that exchange information have different authorizing officials within the same organization, the organizations can develop agreements or provide the same information that would be provided in the appropriate agreement type from CA-3a in the respective security and privacy plans for the systems. Organizations may incorporate agreement information into formal contracts, especially for information exchanges established between federal agencies and nonfederal organizations (including service providers, contractors, system developers, and system integrators). Risk considerations include systems that share the same networks. | |||

| System and Communications Protection | |||||

| Boundary protection | SC-7 | Managed interfaces include gateways, routers, firewalls, guards, network-based malicious code analysis, virtualization systems, or encrypted tunnels implemented within a security architecture. Sub-networks that are physically or logically separated from internal networks are referred to as demilitarized zones or DMZs. Restricting or prohibiting interfaces within organizational systems includes restricting external web traffic to designated web servers within managed interfaces, prohibiting external traffic that appears to be spoofing internal addresses, and prohibiting internal traffic that appears to be spoofing external addresses. [SP 800-189] provides additional information on source address validation techniques to prevent ingress and egress of traffic with spoofed addresses. Commercial telecommunications services are provided by network components and consolidated management systems shared by customers. These services may also include third party-provided access lines and other service elements. Such services may represent sources of increased risk despite contract security provisions. Boundary protection may be implemented as a common control for all or part of an organizational network such that the boundary to be protected is greater than a system-specific boundary (i.e., an authorization boundary). | |||

| Protection of Information at Rest | SC-28 | An agency should implement measures to protect the confidentiality and integrity of system and user information while located on storage devices. This information can be protected through cryptographic means, file sharing scanning, etc. Since privileged users job functions may entail performing administrative and security related functions on this information, enhanced protection increases an agency’s privileged user management capabilities. | |||

| System and Information Integrity | |||||